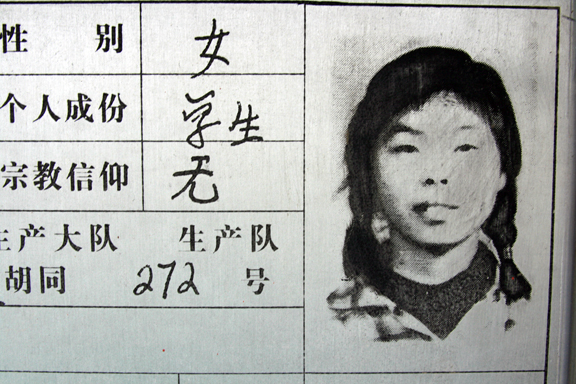

A large concrete star guards the entrance to Fan Jianchuan’s Educated Youth Museum in Anren, an hour outside of Chengdu. On each side of the star is a plaque, memorializing ten young women who burned to death in their dorm in 1971. The plaques show the school reports that all educated youth and Red Guards filled out before they were sent down to the countryside, stating their hometown, age, positive attributes, reason for joining the Party, as well as their own negative traits and areas for improvement. They’re all young girls, none over 18, and passionate about the Revolution.

“The resplendent red sun rises in the east. The first year of the great 1970s is past, now we welcome the beginning of 1971,” writes Fan Jin Feng in her report. “I will summarize my efforts to study Mao Zedong Thought during 1970 below, but first let me mention my deficiencies, speaking out of turn in class, for example. This is one of my deficiencies. But I have also done well in some areas …”

You can’t help but wonder who she could have been, had she not been sent to Yunnan to serve the Revolution.

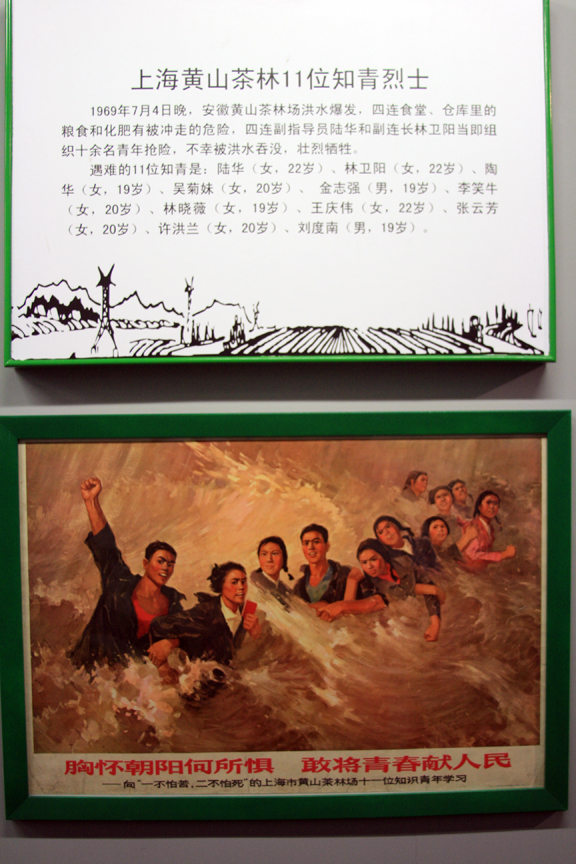

No Red Guard set the fire, for all we know, yet still the whole museum leaves the impression that no matter how these children died, it was the Revolution that ate them. The entire museum is devoted to the 20-some million urban youth that were sent down to the country during Mao’s last ditch effort to indoctrinate the country. Several installations, including most of the second floor, show the tragic, heroic faces of young people drowning in a flash flood trying to bring grain to peasants, burning to death in a brush fire in Mongolia, or just sleeping in their dorm rooms, dreaming red dreams.

The images conjure up feelings of strong bonds, revolutionary joy and, above all, tragic waste. The beautiful, intelligent, ardent faces, all young, all dead before their time in accidents or disasters, are an ironic symbol for the whole era. The best of the nation becoming martyrs of the revolution, or worse, living on knowing all they did during the Red Era, the dreaded Cultural Revolution, was for naught.

The Best of Times, the Worst of Times

The first two people I met when I came to China in 2000 were survivors of the Red Era. Luo Shifu, the local handyman, was what you would call a “common laborer” – not much culture to him, but tons of wisdom. When he spoke of the Cultural Revolution in Chongqing, he always pantomimed shooting people.

“Ka Za! Ka Za! That’s what we did in those years. We all had guns. Everyone fought everyone!”

He had a gleam in his eye, when he stood up from the lunch table and showed me how he held his rifle. There was the brotherhood of struggle for him back then, that faded away with the Opening Up and Reform that followed. After he finished talking about the 8.8 Gang and others who fought over Beibei and Chongqing’s port, he would sigh and sit back down.

‘Those were terrible days,” he would admit. “All the schools were closed, no one had enough to eat. A crazy period.”

Then he hefted his tiny glass of baijiu and we toasted to the old days, good and bad. He never seemed too depressed about the whole thing. He went about his daily work with an irrepressible cheer and he always had a kind word for me. I drank his baijiu all the time, evenings with him were a glimpse into the simple routine of a contented man.

The second person I met, who also went through that period, was Mu Laoshi, a tall, balding man who spoke excellent English – in the sticks of Chongqing no less – but didn’t really have much to do around Southwest Agricultural University except drink tea, smoke cigarettes and engage me whenever he could. When he spoke of the Red Era, his whole frame slumped and an aura of failure, bitterness and indignation wafted out and took me in. He asked me for money or favors every now and then and always seemed on the edge of any conversation, leaning in, trying to glean a few morsels.

“A total waste, those years. No one could go to school, we were unable to train for anything. For me, a foreign languages student, it was especially hard. If it weren’t for those years … ”

I find the same dichotomy playing out with others that told me about their lives in the 1960s and 70s. Some were content, others were bitter, but mostly each person had a healthy dose of both. One man told me with unconcealed pride about eating mud and bark for days on end. When he finished reciting the hardships he and his family stoically endured, he proceeded to curse Mao, the Party and the entire Communist Revolution, all the way back to that maniac Marx himself. My father-in-law was one of the lucky few who were able to go to college in the early 1980s, but even he speaks glowingly of the guns and the roving bands of revolutionaries that ruled the land during that time. He smiles wide and confidently in pictures from those days, like everyone else did, it seems.

The Educated Youth Museum is lined with smiling faces. They peer out from trains headed into the countryside, stand out from a group of Tibetan herders, gather together for group shots along a riverbank or in the small kitchen of some peasant’s house. Fan Jin Feng sounds positively revolutionary in her report, written just a few short months before she died:

“I am very earnest when laboring in the factory, humbly accepting re-education from the workers,” she writes. She was 17 at the time. Was she truly earnest, or just writing what needed to be written at the time? She continues: “From today on I am determined to obey Mao Zedong’s words in everything I do, raise up the Great Red Flag of Mao Zedong Thought, flexibly study and use Mao Zedong Philosophy, constantly improve my revolutionary thinking, constantly improve my worldview, and strive to be a solid and dependable apprentice of the revolution.”

It’s not hard to imagine a young girl intoxicated by a movement heading off to the countryside, waving to her proud, teary-eyed parents from the rail platform, gripping the Little Red Book in her hands.

Some of those revolutionaries never came home. I met a band of old Educated Youth in the hills of Liangshan, the Yi stronghold of southern Sichuan, and they had been there since the 1960s. Some of them had married locals, but most of them were just happy to be away from it all. They ran a few shops selling stationary and petty groceries and not one of them cared a whit for their hometown, Chongqing. The band seemed lost in time, and quite contented at that. We’re not going back, they told me, there is nothing there for us … and we are happy here.

Some went on to greatness. Walking through the third floor of the museum is like viewing a Who’s Who of contemporary Chinese society. Politicians Wen Jiabao, Xi Jin Ping, and Bo Xilai; actors and actresses like Ge You, and Li Xiao Qing; the painter He Duo Lin and businessmen like Liu Yong Hao, even Fan Jianchuan himself. Everyone between the ages of 45 and 65 experienced the Cultural Revolution in some way or another and the effects of that period are deep and abiding. Those days and the people who went through them define modern China, much more so than their connected children, in my opinion.

An Obsession

Fan Jianchuan was just a kid when the Cultural Revolution turned its sights on his father. When he was nine, his father was accused of anti-revolutionary activity and as he stood in the docks, he told his son to “collect every scrap of paper on these allegations that you can” and that’s what little Fan Jianchuan did. He hasn’t stopped since. He is now one of China’s most vigorous collectors, receiving more than 100 containers of stuff each year from around the nation. He has agents in every province, in every major city, and they help him sniff out collections and buy them up.

“The museum cluster hold about 1% of my collection,” he told me. “I have tons of stuff waiting to be displayed.”

The Fan Jianchuan Museum Cluster is the largest and most provocative privately owned collection of historical artifacts in the entire country. The Educated Youth Museum alone should raise eyebrows with your average hardline politico, but not only does the museum operate unmolested, but the visitors I saw – and the ones who left their mark on the guest book – seem to identify with the symbology Fan has infused into his displays. The irony and the waste are not lost on anyone who lived during that period, or it turns out, on today’s young people. I saw an older man leading his teenage daughter through the museum, telling her of this and that, and it was clear to me that he was telling his story to a girl that grew up on a completely different planet. Yet she listened and, to her credit, she seemed interested.

A young teacher with me on the trip to Anren laughed away the installations and told us she knew nothing of that period and didn’t want to know anything. But as she read about young girls braving floods and saw the pictures, her attitude slowly changed. She started pausing at each image, each description. Instead of texting, she murmured her sympathy and appreciation.

“Gosh, they’re so young, they look like my students age,” she said, when we stopped to look at the 11 youths who died trying to save fertilizer during a flood. “But my students would never try and do what they did. No way.”

The cluster includes several other fascinating installations, most powerful for me were the Wenchuan Earthquake Museum, which Fan put together not a month after the tragedy, and the Plaza of the Martyrs. The martys are cast-iron, life-like statues of the major figures of pre-Liberation China. Generals that fought against the Japanese stand next to Revolutionaries who ran with Sun Yat-sen while Chiang Kai Shek and Madame Song smile benevolently just a few paces from Mao Zedong and Zhu De, one of the Communist’s greatest generals. They all face one direction and each expression is a mixture of determination, hope and zeal.

“This is where I come when I feel low,” Fan said. “I come here and look at these men and women and I realize that I am just a small, small person with a great responsibility. These statues inspire me and keep me going.”

Keep going where? When you ask him, Fan says he wants to be the biggest collector in the world and the first to open up a museum for traitors during WWII, or the first to create a museum dedicated to corruption. But when I walk around his cluster, I get the feeling Fan is exorcising demons. His own and the nation’s, but primarily his own. He designs every installation and although he insists that the objects speak for themselves, his touch is everywhere to be seen. He wants the nation to face itself.

“A mature nation must be able to look at things rationally,” he tells me. “For a nation to grow, people have to be rational, people have to be allowed a different point of view.”

In the middle of the discussion, he jumps up and grabs a vintage Mao Zedong pin and hands it to me.

“During the Red Era, people would pin these through their bare skin to show their devotion to Mao and to the Revolution,” he declares.

His expression slides between revulsion and awe and he demands I put the pin on right then and there. I can’t help thinking that he, along with everyone else over 45, suffers from a long, drawn out form of post traumatic stress disorder. I look down at the pin and am reminded of passages in Yu Hua’s novel, Brothers, in which villagers march up and down chanting slogans and anti-revolutionaries commit suicide with screwdrivers and primitive nail guns. I think of people beaten to death in the street while hundreds look on and do nothing. The horror stories are endless. Who turned his back on whom; who died alone and forgotten; who was executed by zealots. Fan hints at deep, dark secrets in his vault of artifacts, but many will have to wait, he says, because those who committed the crimes are still alive. When their dead, then we can speak plainly, he explains.

For 30 years these men and women sent down to the countryside or left behind in cities to fight over blocks and wave red flags have had no one to talk to. No one wanted to remember their deeds or misdeeds and when the topic came up, everyone muttered “insanity” and moved on. As a foreigner, I am a safe bet for anyone who wants to bring up those times. I have heard cabbies and bosses tell their tales of woe and repression. No one ever admits to killing or persecuting anyone, but that’s to be expected: Not one German knew what was happening to the Jews during WWII, right? It took generations for Germans to get out from under their collective guilt, China is no different.

Fan says his obsession is collecting, but I think that obsession finds roots in the horror of seeing his father pilloried and hearing his words, “collect everything … ” We cannot underestimate the power of that era and the hold those days still have on people today. When I ask my friends why their mothers are so clingy and controlling, they say that back when they were young, no one cared about them and they had nothing. When journalists trace back the conflicts that brought down Bo Xilai, they find age-old grievances and festering wounds.

In China, insulting someone’s ancestors is a big deal, as is sweeping the tomb of generations past. It might do Westerners good to take a step back and consider filial piety from a Chinese standpoint. Try and imagine being in a society in which the old rule by virtue of being old, the past is revered for being the past and then imagine having all that shattered in a few short years of madness. I feel in my bones that Fan Jianchuan’s obsession is not just his own, it belongs to all of China – those that went through the Red Era, their sons and daughters, and the Little Emperors they dote on so fiercely.

Today’s leaders would love for everything to remain covered until every last victim from the 1960s and 1970s is dead and gone. But Fan Jianchuan’s obsession, Mu Laoshi’s bitterness, the memory of Fan Jin Feng, Lin Zhao, Liu Shaoqi and Bo Yibo won’t let the past rest in its shallow grave.

“Some of us hate those years, some of us think it was a great experience,” Fan muses toward the end of our interview. “The good and bad is intertwined within every person, we all have this contradiction within … I do as well. When I die and the museum is still here, I still won’t know the truth, but at least it will be there for history to judge, and that is enough for me.”

Wow. Great interview, Sascha. Did you ever get a chance to check out the propaganda museum in Shanghai? It’s just a little ol’ thang (nothing like this place, clearly), in the basement of an apartment complex.

Real dope, though, and there are some pretty open discussions of some of the more controversial periods of Chinese history. I think what Fan said about a mature nation facing it’s past is right on. Every nation struggles, for sure, but it seems like China is in a much more heightened state of denial than it should be at this point in it’s development.

no i never made it to that museum, but the discussion is definitely going on, everywhere all the time. Just need the leadership to have the balls to open the floodgates of catharsis. But knowing this society, opening the gates would just lead to more insanity. Maybe the Party is right …

I visited the museum cluster in 2008 with my dad. We met Fan Jianchuan and he showed us around. He took us into one of his warehouses–he really does have tons of stuff that’s not on display. He sent us off with a free 猪坚强 T-shirt (he had recently purchased 猪坚强 for the Sichuan earthquake museum). It’s great that he hasn’t been stopped from this important work.

Great story, please could you supply the address for this wonderful place. I’m intrigued!!

sure it’s the only thing in Anren Town really – the place was fields before Fan Jianchuan showed up – and you can get to Anren via bus from Xinnanmen Bus Station. I would recommend renting a car and driver, for convenience sake. Anren is just under 2 hours outside of Chengdu.

Inspired by this article, I’m going there tomorrow. I just want to point out to other readers that Anren is reached by bus from Jinsha Bus Station, not Xinnanmen. This info comes from the tourist office next to Xinnanmen as of this morning. Glad I happened to be in that neighborhood and dropped in to ask.

thanks for the info, I actually hired a car. here is a video my friend made while at the museum:

http://v.youku.com/v_show/id_XNDQ4Njg5ODQ0.html

how was your trip?

Potent piece. Despite all the years I’ve been here I haven’t really heard folks open up about this period other than their dismissive attitudes towards naive 九龄后 post 90‘s generation.

Stories reminded me of Feng Jincai’s “Voices from the Whirlwind”

http://www.amazon.com/Voices-Whirlwind-Feng-Jicai/dp/039458645X whose’ oral histories of the cultural revolution left a larger impression than anything I read in chinese sociology courses in college.

Glad to here that your texting teacher sharpened up a bit and was moved by the museum, but it does seem that there is a sweeping tide of apathy among china’s youth, yet us foreigners want to get our fingernails encrusted in on all the “dirt”.

Dig it

Great work, Sascha – thank you! One question: Where does Fan Jianchuan get the money to create and continually augment this museum cluster?

he was a government official in Yibin in the 1990s, reaching vice-mayor, and then went into business. After 10 years of business – including real estate, a gas station, and other stuff – he started on museums. He has sold almost all of his property and now only has the museums and a small office in the city, he lives out in Anren. So from what I could gather, this truly is his life’s work.

and the museums of course charge entrance fees

Interesting side note, the Cultural Revolution museum at the Anren cluster was designed and built by an avant garde Chinese firm, Feichang Jianzhu:

http://tinyurl.com/d9ut6kq

courtesy of Adam Mayer …