Note: This is a guest post contributed by Mandarin Blueprint, a Chengdu-based company which guides students towards proficiency in the Chinese language around the world. This post is a follow up to a previous post on a more fundamental aspects of learning Chinese, which is pinyin.

Most of the time, when people talk about their Mandarin Chinese ambitions, they focus on spoken fluency. An excellent goal, and we tip our hats to all who pursue it. However, we’d contend that an even better goal is to seek literacy in Chinese. It might not be too shocking to find out that these two goals are secretly best friends, but this article will focus on how to avoid becoming an illiterate person. Or, in Chinese: a 文盲 wénmáng” (literally “literature/culture 文” “blind 盲.”)

Most of the time, when people talk about their Mandarin Chinese ambitions, they focus on spoken fluency. An excellent goal, and we tip our hats to all who pursue it. However, we’d contend that an even better goal is to seek literacy in Chinese. It might not be too shocking to find out that these two goals are secretly best friends, but this article will focus on how to avoid becoming an illiterate person. Or, in Chinese: a 文盲 wénmáng” (literally “literature/culture 文” “blind 盲.”)

The Usefulness of Literacy

Spoken Mandarin is useful in many situations, but it’s easy to forget how valuable it will be for your literacy in Chinese to allow for quick texting. When you can read and write in Chinese, suddenly a new world of expression and opportunity opens up to you.

Apart from the enormous advantages you gain from texting and being able to read contracts, you can also easily navigate Chinese apps (e.g., ordering food, ordering a car, buying things with WeChat & Alipay, using Baidu maps, etc.). The Chinese internet economy is incredibly rich and diverse, but you won’t be able to participate in the majority of it without being literate. We even know people with decent spoken Chinese who’ve lived here for years, but they don’t have a Taobao account. What a bummer, Taobao is amazing.

Pursuing Literacy Gives You Motivation

When you pursue literacy, Mandarin learning becomes much more like a game. Why? Well, there are a finite number of characters you need to learn and a limited number of words. Your “new word count” serves as a points system, but those points aren’t just the arbitrary construction of a game developer. Those points represent real and tangible tools of communication. Pursuing the spoken language, sadly, offers far fewer measurable metrics.

Without Measurable Metrics, Doubt Creeps In

Regardless of what you are learning, there is one thought that kills your motivation: “Is what I’m doing even helping me make progress?” As soon as this thought enters your brain, you start to doubt. Doubt is a *powerful* emotion. The moment you feel it, you begin to question the choices you made that led to your current goals. Sometimes, that doubt is reasonable. It helps you adjust your path towards something more productive. However, if you start to doubt too much then you the next thing you know, you’re thinking “Why did I even start to learn Chinese? Why did I think I could do this? I should just cut my losses and move on with my life.”

Not only do we empathize with this cycle of thoughts, but we also lived it. In a sense, you could argue that it was the desire to help people avoid that doubt that spurred us to start Mandarin Blueprint. What if we could kill the doubt?

Reading Skill Transfers to Speaking Skill

It wasn’t until the two of us started reading longer texts that our Chinese became 运用自如 yùnyòngzìrú – ‘(idiom) to handle very skillfully.’ Why? Well, think about what it’s like to speak your native language. Technically speaking, there is a lag between deciding what you want to say and speaking aloud, but that lag time is almost imperceptibly short. As a result, it feels as if you are discovering what you want to say the moment you are saying it. The best way to reduce the time it takes to realize what you want to say and speak aloud is to read. Reading increases your level of vocabulary faster than any other method.

The reason reading is better than listening to acquire vocabulary is two-fold:

1. You have time to go over what you don’t understand.

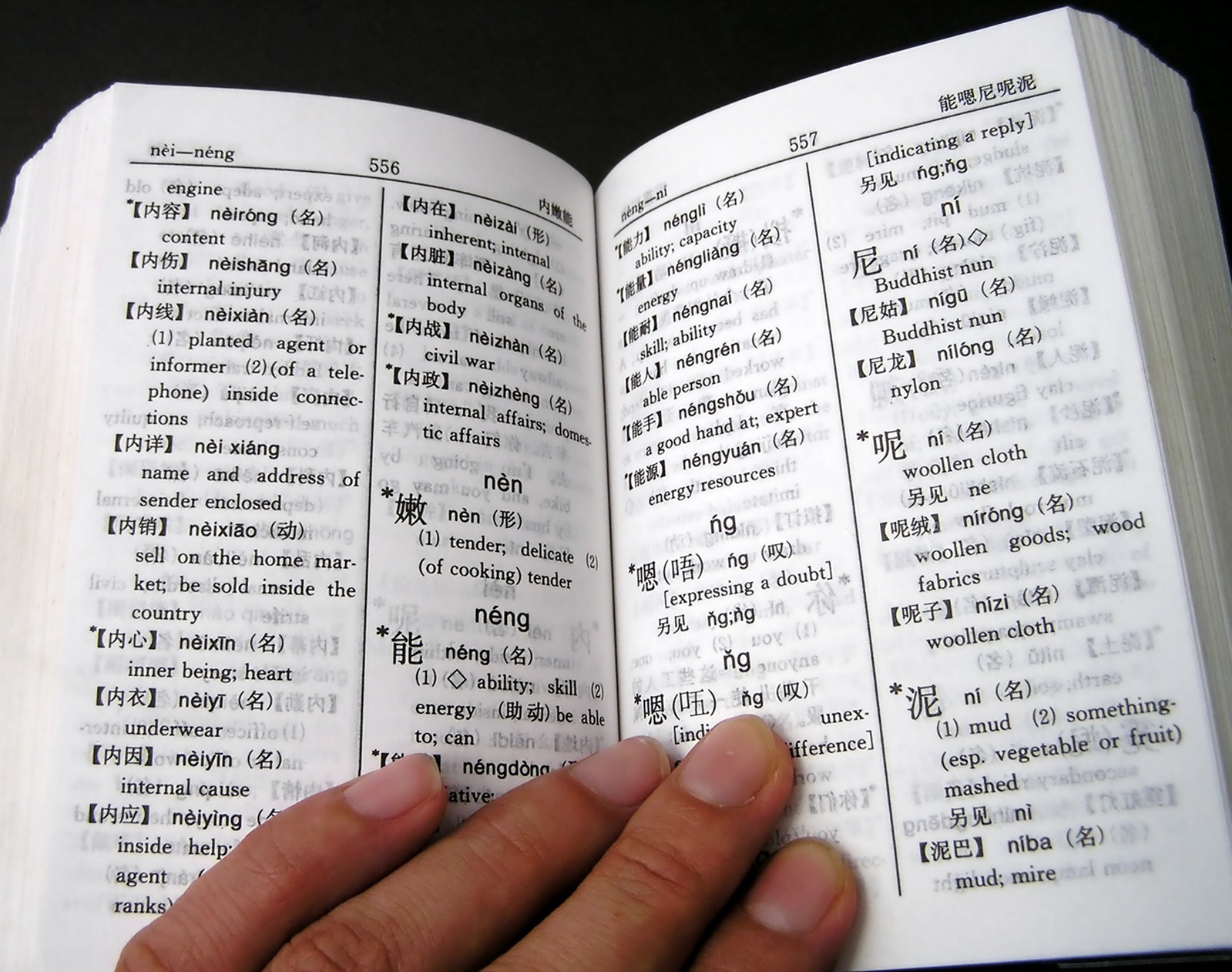

If you’re in a conversation, you will drive your Chinese friends crazy if you asked them to repeat themselves every time you didn’t understand a word. If you’re listening to an audio podcast, rewinding to the exact moment you didn’t understand may not annoy anyone, but compared to moving your eyes from one sentence to another it’s practically sloth-like.

2. Mandarin has more visual distinctions than audio distinctions

We can’t tell you the number of times we’ve heard people say a word and assumed it was something else. There are only approximately 409 syllables in the language, and so when someone says 直到 zhídào ‘up until’ instead of 知道 zhīdào ‘to know,’ you’re far more likely to mix up what they’re saying. However, you’ll notice that 直到 & 知道 look nothing alike visually. You won’t confuse them when reading, that’s for sure.

Since reading is better than listening for acquiring vocabulary, that means that the time it takes to *find the word you need* diminishes. That’s why reading skill transfers. To be clear, ‘finding’ the word isn’t an intentional process. The experience is more like a delightful discovery. “Oh wow, I just said that word in context for the first time. It just popped in my head!”

The conclusion is this: the ability to read Chinese makes your spoken Chinese much better.

BTW, Reading is the Best Part

All of the above logical arguments, although valid, fail to express that reading Chinese is what makes you stand in awe of the language. Spoken Mandarin isn’t unpleasant to listen to, we quite enjoy it, but we’d contend that it’s the most beautiful language to read in the world. Why deprive yourself of the best part? Aside from physical books and signs and text all around China itself, there is another digital world of communication and editorial to explore.

Reading and writing Chinese has been the most fun and enjoyable part for me. Part of my daily routine for a few years has been to read articles in Chinese, which I find provides a good challenge with insight into Chinese culture and language.

These are some of the sites I read:

– https://www.ifanr.com/ technology site, like The Verge

– https://cn.nytimes.com/zh-hant/ NY Times

– https://www.gamersky.com/ Game industry news

When you’re just starting out, you can get into reading on these sites using a browser plugin which translates Chinese into English via mouseover. It’s great to also take words or phrases you can’t read and make them into Anki cards which you study later.