This Q&A is part of the Chengdu Stories series of interviews with people living and working in Chengdu, telling stories of their lives in the Sichuan capital city. This interview is with Reed Riggs, Ph.D., Chinese instructor at Brigham Young University, Hawaii. Reed lived in Chengdu for five years, and Yangzhou and Guangzhou for two more years, before returning to the United States.

This Q&A is part of the Chengdu Stories series of interviews with people living and working in Chengdu, telling stories of their lives in the Sichuan capital city. This interview is with Reed Riggs, Ph.D., Chinese instructor at Brigham Young University, Hawaii. Reed lived in Chengdu for five years, and Yangzhou and Guangzhou for two more years, before returning to the United States.

1. How did you first arrive in Chengdu, what do you remember most about the city, and where did you go after you left?

I had just finished my BA and I wanted to “get good” at Chinese, mainly in speaking and reading. The food, of course, caught my attention, and I continued loving it more and more as the years in Chengdu went on. You and I were part of the Chengdu Gastronomic Society during my later years there. It really helped to have eight or so friends together at a restaurant so we could order more dishes, each person could suggest something maybe someone else in the group hadn’t tried (or heard of) before. The variety of flavors in dishes from different regions across Sichuan really stood out to me. I tried to watch people cook whenever I could. I would stand in a friend’s kitchen doorway asking what names and brands the ingredients they were as they cooked, and also when exactly to add each ingredient to the dish.Since moving back to the US, I try to keep a number of Sichuan spices and sauces in my kitchen, and I’m very specific about the brands. A lot of similarly named ingredients that I can buy in the US aren’t the right brand, and the taste is completely different.

Another feature that I loved about Chengdu was the many regional dialects. It caught my attention right away. I spent a large part of each day just listening to people talk at the table next to me at a restaurant, or my students during a break. I would listen for differences in how people spoke by gender, regions people came from, age, emotions, and other differences. I have always loved languages, and I especially loved how people spoke in and around Sichuan.

People in Sichuan tend to be very playful when they speak, and they use their language as part of that playfulness.

2. Is there anything about Chengdu that you feel has stayed with you in particular?

The cooking. I still cook with Meile brand Xiang La Jiang, as well as the green and red varieties of Hanyuan huajiao. I typically make Xiang La Yu (香辣鱼) and Ganbian Siji Dou (干煸四季豆) a few times a week. When friends go back to visit China, I sometimes send them a weblink to a Dang Dang product page, and ask if they can bring back jars of Meile brand Xiang La Jiang for me because I can’t buy it in the US.

3. You published a number of articles on Chengdu Living about learning the Chinese language. Where did your studies take you after leaving?

After leaving I applied and was accepted to the University of Hawaii to start a Ph.D. in Chinese Linguistics. I enjoy academic settings and I loved everything I learned in that program. My research now focuses on areas in language teaching and areas in theories of learning that I believe can help people learn.

The theory side focuses on how the human brain works like a big statistical computer, but the way scientists have been testing these theories looks a lot like certain kinds of teaching that a lot of teachers (mostly of Spanish, French, and German) are using in their classrooms across the US. A small number of Chinese teachers are re-working these teaching practices to fit the needs of Chinese language learners, and I’m working with them to help Chinese language teachers and learners, and show researchers and teachers that their work can be useful for each other. Teachers can better understand why their teaching has the effect that it does, and researchers can see the effects of certain types of teaching to confirm or disprove theories of effective learning.

4. How was the transition from student to teacher?

I was never a student in a language class while in China, except for when I studied abroad in Beijing for a semester in 2003; all of my studies in Chengdu were at home, at work, and around town. In my first years I bought textbooks at my level, and I just worked on reading and building up vocabulary, through through lots of reading. Through work and really any time leaving my apartment, I would talk with people about various topics of interest.

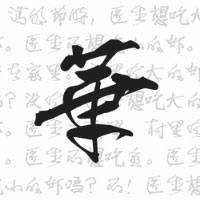

Later I read easy Chinese novels. I found the fiction of Lu Xun and Yu Hua to be something I could more or less follow and enjoy. I loved going to the giant book stores, like the one at Chun Xi Lu, and later the giant one that opened near Wu Hou Da Dao. I could spend hours in there looking at maps, educational posters, book titles, and random pages in books that caught my attention. As a teacher in university classrooms in Hawaii, first at UH and now at BYU-Hawaii, I use classroom time to train students in reading and conversation. I give little “popups” here and there about my experiences in China, and really anything that I find fascinating about China.

5. Do you have any feelings on how Chinese language is viewed in the US, and if the perception has changed at all?

Research on different motivations for studying languages — Patty Duff comes to mind — has found that whereas students choosing to study Spanish in the US tend to say they do so because Spanish can be useful, students choosing Chinese describe their motivation as wanting to learning something uncommon, different, and adventurous.

My own motivation for starting to learn Chinese was that I thought it would be too challenging to begin on my own. I wanted a teacher to guide me through the beginning. I’m now hearing about more immersion programs for elementary age children in the US, especially in California. In Hawaii, my classes have usually contained around half or more “heritage” speakers. These are people who grew up with someone speaking the language at home. Their speaking ability can range from fluent to near-zero, but they all typically need to work on basic reading and writing.

The University of Hawaii has been running the Hawaii Language Roadmap Initiative to contact local businesses to survey what languages they need their staff to speak. People proficient in both Chinese and English are in high demand for the workforce here, and this is good for teachers and students in classrooms, to make goals of learning more clear and focused.

6. What have been some of your biggest epiphanies in achieving mastery in the Chinese language? What are the most common mistakes or mishaps that leaners commit?

I’ll numbers these here:

- A paragraph is not simply a collection of new vocabulary to hunt through and memorize. I realized after I moved to China that during my prior four years of Chinese “reading,” I was never actually reading at all. Instead, I was performing a kind of “organ harvest” for vocabulary, making no effort to really track the author’s perspective and purpose through the ongoing discourse across the sentences and paragraphs. The sentences could have been scrambled randomly and I would not have noticed any problem in the writer’s style or message. Now, I make an effort to keep track of the author’s purpose and arguments.I try to build a big mental picture as I read, and I try to visualize details to add to that picture as I continue through the text. If a new fact doesn’t fit my picture, I wonder if my picture is missing something that I’ll have to go back and read for, or if the author intended to surprise their audience.

- Language is primarily learned through listening, and only secondarily through reading (speaking and writing also benefit from practice, but I’ll get into those below). I teach new students through ear training first. I ask fun questions in class, and they have to understand and then offer fun answers. I notice their pronunciation closely mirrors how I have been saying it — how they heard it. But the students who mainly learn from reading pinyin outside of class develop what one teacher has called “Pinyin accents”, based often on how they would guess Pinyin letters to be pronounced in English.For example, students say /tai/ for “ti”, and /kao/ for “cao” and tones are either replaced by English intonation, or pronounced robotically, character by character, without the kind of sentence-level flow that I hear from students who have been listening a lot.

- Word-lists and grammar descriptions (textbook content) can be useful for organizing lessons, but simply explaining textbook content to students and requiring that they memorize it for tests does little to nothing to build up the kinds of knowledge needed to participate in conversations, read extended texts, or otherwise use the language for any social function. Instead, it’s the input—the language we hear and read—that builds this knowledge, and speaking and writing builds these abilities in their appropriate contexts (for example, phrases we use to order food are different from phrases we use to meet someone’s parents).A classroom can be a perfect place to make sure learners are hearing, reading, understanding, and using the language in contexts that are relevant and motivating for them, and, importantly, so that they can also use the language outside the classroom.

- Shut up and listen. I watched friends (and myself for my first years in China) adamant about “practicing” Chinese with Chinese people. This usually meant talking over people, and saying things that weren’t logical or coherent with what the Chinese participant in the conversation had been saying. Thinking “I’m really going to get better at this language if I can just use this time or person to practice my Chinese speaking” is no less selfish than local people asking to practice English with foreigners.In my final few years in Chengdu, I started to notice Chinese people talking to me far longer when I simply looked at them and listened. Similar to when I was reading, I would try to let their words paint a picture in my mind, and when I noticed a gap in that picture, I would on occasion say that part back to the person to try and get them to clarify. It was when I started listening more that I also noticed people sharing more personal stories about stress at work, home, friendships, business, pets, and other topics close to their lives.I don’t think being a good listener is unique to Chinese society and culture–I think it’s human and universal for people to enjoy being heard. I also notice now that when I want to express something emotional in Chinese, a have a lot “resources” in my head as memories of what Chinese people have said in my experience. As I help to teach a new generation of Chinese-speaking foreigners, I like to share stories like these with them in the hopes that I can send more socially aware foreigners to China..

7. How do you view life in China, after having lived in Chengdu for years?

Life in China was loads of fun, and I certainly miss the people and the food. In fact, food is still a reliable topic of conversation with Chinese people I meet in the US. We all miss the food in China! I’m working with boarding students from China here in US right now, all around 15 to 17 years old. It’s a good reminder to me about how fast times—and people—are changing in China. It’s hard to keep track of which changes are simply temporary, that young people will grow out of, and which are generational in the sense that when these people turn 30, they will be significantly different than their parents at age 30.

My career for now is keeping me in the US. I’m excited about a local community of language teachers I’m working with. We are all coming from public and private K-12 schools and universities and of many languages, including Chinese, Japanese, Hawaiian, Samoan, Ilokano, Spanish, French, German, and a number of native American languages. I have helped organize several large workshops as well small gatherings for us to demo teach and offer feedback to each other. The linguistic diversity and close-knit community in Hawaii is part of what’s keeping me here.

8. You’ve published a number of books for Chinese language learners and readers. How did you get onto that project?

I registered Reed Riggs Publishing about a year go in Hawaii, before taking my new job teaching at BYU-Hawaii. I talk a lot with teachers who write beginning-level novels in their classrooms, for what they call Free Voluntary Reading (FVR) libraries. A few years ago I spoke at the American Council on the Teaching of Foreign Languages (ACTFL) about a need for these teachers to use professional story-writing structures.

This comes back to my experience with not reading texts for the author’s intended message, imagery, etc., as I ask—did the author intend for the reader to gain anything at all besides linguistic knowledge? Texts written for learners at worst are only written for language practice, and at best, so far as I have seen, teach about culture, history, real people, and also try to be somewhat entertaining. As I was not in a classroom a year ago, my mind was also not primarily in classrooms. Instead, I was thinking about books I would want to read such as The Three Body Problem, as I enjoy science fiction. I watched—and still watch—a lot of horror and sci-fi movies on Netflix. I have always loved the heightened socially commentary and self-reflective criticism that sci-fi tends to offer, bundled along-side the robots and aliens. I love watching the kinds of introspection that horror can offer. Meanwhile, I am usually bored by romance movies, but I see that many people love those kinds of stories.

Genre-based TV, movies, and novels, and video-games, are billion-dollar industries that provide stories for people of all ages, formats, and genres. This is what I want to bring to novice- to intermediate-level Chinese reading audiences. I recognize that people who only speak and read a little of a language typically want to improve in their abilities in using the language, so that remains one of my goals. Though I think it’s important to put the entertainment goals close to and above, the learning goals.

My top goals are the normal goals of good story-writing: entertain audiences, teach better ways to see the people around us, teach better ways to help the people around us, and inspire future creativity. Keeping the language simple so beginning learners can understand it serves as gate for both the Good Story goals and for the Language Learning goals. By providing content that attracts people in the same ways that Netflix and graphic novels do, my hope is for people of many ages and genre-preferences to get into enjoying content in Chinese that will simultaneously help them acquire Chinese.