Yang Mian led me downstairs to his studio in the giant loft in Hetang Yuese belonging to his family, late on a Spring evening. I immediately had the sensation of treading into Dinosaur territory. The space itself feels like an aircraft landing pad, the over-sized paint tubes and palettes looking cartoon-like in their bins. He left for awhile to get some coffee, and I basked in the towering glow of an almost story-high painting from his CMYK series. Its thousands and thousands of brightly colored dots against the canvas made me blink.

There is a critical legacy in Yang Mian’s family: his father, also an artist and intellectual, was labeled a Rightist by the CPC before Yang Mian was born. In 1996, for his third-year solo exhibition as a graduating student in the Sichuan Fine Arts Institute, Yang Mian dedicated an installation to his, then deceased, father. It was entitled Sacrifice to the Lotus, and it bears little resemblance to the kind of work Yang does today. In Eastern tradition, he borrowed the image of the lotus to express his love for his father, their relationship, and his father’s death, placing the images in symmetrical form. White paper lotus flowers lay on the gallery floor, surrounding five paintings and reproductions of lotuses.

While he is primarily a Pop artist focused on culture criticism, this college exhibition showed that the young artist was trained in the same manner as all other art students in China- replicating images from the Western canon, but following in step with tradition. The point at which Yang Mian ultimately did away with tradition, and with the advice of his many critics, came after. In college he stuck to the accepted Western forms, like Expressionism. This kind of borrowing is something yet to be interrogated in contemporary China, which is still witnessing the development of its artistic voice in a new global society. Yang Mian stands for this interrogation, and for standing out- amidst a competitive world art market- with irreverence, insight, and departure.

The Incisive Line

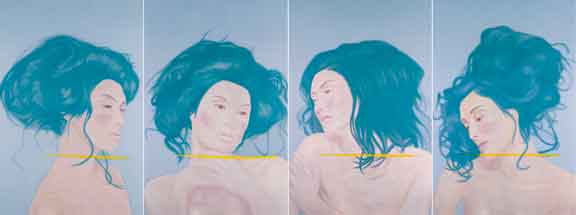

As I look through a book containing Yang Mian’s collection from Beauty Standard, going back to 1997, I’m first bored by the large number and repetitiveness of the images (finished in 2005). I see only faces- effortless, gliding, monotonous. Women tossing their hair with accidental charm, giggling, subtly entranced by how uncomplicated their life is …

I say “life” as if they were all one woman. Of course, they vary in style, number, and gesture. Snapshots of these women- or girls, really- come from magazines and advertisements on buses and billboards seen all over China, some in Hong Kong, and Korea. But their presence is known to every city-dwelling member of modern civilization. They reside in all countries, all cities, all cultures- ethnically altered, they play the same role as real people in a parallel society, gently circumscribing the most frivolous channels of our material existence- inviting anything but critical dialogue.

That is, until Yang Mian started interrogating them.

Coming into focus, a thin, almost reflective, yellow line bisects- or rather slightly inflicts- each beautiful, frivolous face. At first I didn’t see this, since the paintings themselves are so washed out, yellow almost blends in. Is the yellow a flaw? An accident of the light?

In contrast to his portraiture, Yang Mian’s yellow lines leave a tactile, weighty impression. In other words, they’re real. One thin little strip of realness punctuates each work. This realness competes with the unbelievability of the backing image, so confusion results. Of necessity, it creates a binary. A binary between what we see and what’s really there. This binary invokes us to question the validity of the image.

When I get to the pages with the red lines, the impression is a little more disturbing. The obvious connotation of a strip of red slicing through a face has a deeper impact, but also, the faces appear even more faded, more ambiguous by comparison. There’s a Stepford Wives aspect to these works.

Probably all of my favorite examples of Yang Mian’s Beauty Standard are left over from the late 1990s. That was when he copied some images from video stills, sometimes using a repeated image of the same woman. The paintings have a fuzzy and distorted quality, just like old video; a true Pop effect, with blatant “image of an image” plagiarism. Of course, they are original, being like caricatures of the women: washed out, no one else would think to paint them that way. And they have Yang Mian’s incisive line slicing through, that line threatening- almost violating- their smiles and contemplative expressions.

After looking for awhile, it came to my attention that the Standard series lines also look like watermarks, rising to about the same level in every painting. Or as indicators of measurement. They also seem to resemble pen marks made on the body by plastic surgeons. One could imagine such strike-throughs appear before breast enhancements. A model, with her head slightly above or at equal level with the marking line, seems to indicate her level of qualification against the hegemonic ‘standard,’ as if she’s about to “go under the knife.”

“The year 2003 was the year of the beauty contest. There were Miss World, Miss Chinese Universe, and countless other beauty contests and beauty ‘festivals’ in China. In this year, it seemed that the “Army of Beauties” dominated the scene…At the end of 2003, the beauty of plastic [i.e. plastic surgery] became the hot issue. Now if you are brave and wealthy enough, nothing can stop you from becoming beautiful” (Dialogue between Yin Yan and Yang Mian).

You may wonder why this is of interest to the male artist, but Yang Mian’s work is not quite about beauty. In his interviews, he reveals an almost scientific degree of reflective social commentary- underscoring our notions about beauty standards, control, and the reliability of images in advertising. While making a clear target of international brands in his image selection, Yang’s target viewer is the average observer. Judgement is a two-way street, and while an image is initially judged by the selector, it may receive its final approval from ordinary consumers. Such judgement occurs in advertizing just as it does in art. If judgements of art are in the eye of the beholder, shouldn’t the artist be concerned with beauty? But he is not. He is concerned with exposing an underlying truth, and will go so far as to offend the viewer to do it.

A Reality Questioned

We see in commercials a conspicuous stranglehold over imagery by the repeated ‘standard,’ seemingly as universal as a language. One of Yang’s questions is: at what point does this language become entangled with society’s own, taking root in and determining our belief systems?

“With the aesthetic standard in China becoming more and more internationalized and Westernized, is our aesthetic drifting even one step further from our own genetic inheritance and traditional standards?” asks the artist in his own statement. “The ‘Beauty Standard’ in my art works comes from those growing up in the [modeling] studios, not from real life; however, people have applied them to their daily lives” (About Yang Mian’s Standard, 2005).

I recently clicked through videos on TheMomsView, a new YouTube channel from the United States that claims to feature “Real Moms” and to address their everyday concerns. I was reminded of this contradiction between commercial-world advertising and real life. If prevalent in China, it’s inescapable in the US. The channel’s representation of motherhood often contains no dialogue, but is suffused with fashion makeovers. All moms appear to come from California. I’m vaguely persuaded that the Hollywood-style beauties are actual mothers of children, based on their claims, but the ‘Comments Bar’ at the bottom of video entries reveals what viewers think:

“Pampered bitches.”

“When does the porn start?”

So commercial reality is not always convincing. But as with every aspect of our lives, commercial values have literally held the child/ mother relationship hostage. Parenting is a public deal, while the moms and babies who are a part of commercialization are impeded with a hailstorm of tailoring, packaging, pruning and plucking. Even the scoop on “Love or Lust” by a comfortable Stay-At-Home, or the cooking and homeschooling tips of a family of twelve, are not enough. A mother’s identity independent of her consumer persona, who is imminently carefree, attractive, and even potentially single, has come under fire, as society’s expectations come into alignment with what it sees in the media.

“There are two threads in my works: one is the questioning of images, the other that of power.” This was stated by Yang Mian in his interview with Yin Yan, covering his growth from childhood in the 1970s to his early exhibitions in the 90s. I like the use of the translated word “thread,” because it describes perfectly how his paintings tie together. “Power” is part of that thread.

“My works have been exploring one question when I use resources from advertisements: who has the right to decide which of these girls is beautiful? Who gives them the power?”

Power determines what we see on camera, stage or magazine centerfold. The endorsee of a product, service, or, these days, a lifestyle, is the tool of whomever gives her the job. And this determines for Yang Mian the direction and ultimate shape of reality. What exists in reality cannot be differentiated from what we see. Indeed, reality is what we see. Our filter is our shared cultural experience.

Yang Mian believes that no beauty experienced in nature can today be free of influence from comparisons drawn to the media, such is the media’s hold on our lives environmentally, politically, socially and ideologically. The goal is to question the believability of the digitally-processed image by stripping it down to its most primitive parts. Yang Mian’s paintings depict an almost completely flat world, devoid of flowery detail. He truly sees this as painting’s role in today’s culture: to depict flatness, superficiality. Only in this way can an image’s validity and reality be exposed and interrogated.

Film, video and animation have already eliminated the need for hyperrealism in art. What is left is to interrogate the image.

The Twisted Image

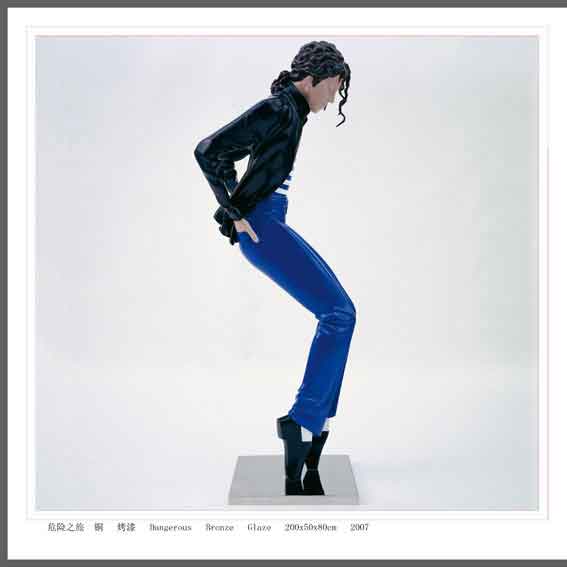

His sculpture also represents a painter’s line of inquiry. “I choose a direct way of making sculpture,” he says. “I take a picture as the model, so that when the sculpture is done, only one side is realistic; the rest is all a bit distorted and twisted. I think painters should make their own contribution to the field of sculpture. For me, that contribution lies in the form of flat sculpture. That matches the properties of objects we know” (Dialogue between Yin Yan and Yang Mian).

Dangerous, part of his collection of Pop Art sculptures, depicts Michael Jackson in one of his glory moments- perched on toes, ready to dance to Thriller. We might say that no sculpted image of Michael Jackson better replicates what we see in the videos, because it’s highly simplified, leaving only the core (memorable) details. What more would M.J. himself have wanted us to recall? This transcription from video to staged photography to sculpting is part of Yang Mian’s signature (and highly laborious) skill set. With his most recent series of artworks, he arrives at perhaps the most laborious process yet.

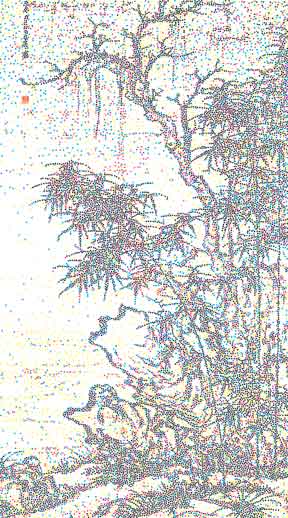

Minghuang’s Journey to Shu was supposedly Li Zhaodao’s masterpiece in jinni shanshui, depicting in color what Emperor Minghuang might have seen on his visit to Sichuan. Done in the style of this Tang dynasty “gold, blue, green” (or “green, blue, white”) method of painting, with mineral pigments, the later replica is a work known all over China- still as ubiquitous as Michael Jackson is today. In a poignant modern take on the listing of colors in a method’s name, Yang has invented a method all his own, naming it after C, M, Y, and K- the color abbreviations, transposing and totally transforming images that people recognize.

Starting with a blown-up copy of the original, every pixel in the image is ascribed a color- Cyan, Magenta, Yellow, and Black to be precise, though the tints are customized. The artist has taken liberties with the pixels’ placement, but he takes great pains in locating and processing them. Every step of the transformation, which ultimately takes months to complete, is done personally. He has performed this transformation on images of many famous works, from Tang Dynasty paintings to European classical works.

The CMYK series represents a new turn in Yang Mian’s focus. With it, he has gone from an interrogation of superficial images in advertising, to a full-on investigation of the status of the image itself- its value, makeup, and origin. If even a great masterpiece can be reinterpreted beautifully through mechanical color-offset image processing, manipulated along different mathematical axes, what becomes of the original work? Is it irrelevant? Are we looking at a piece of art, or the many distorted reflections of a known object? Yang doesn’t answer this, but leaves it for his viewers to determine the status of the individual works.

That CMYK piece is really crazy. It’s difficult to see some of the detail, but it looks really complex. I’m glad that some local artists are using new digital mediums to create art as opposed to strictly traditional mediums. I would love to see more Chinese artists using progressive mediums of expression.

It’s interesting that you say that, Charlie. The CMYK series pretty much combines digital and traditional craft. I asked the artist about his idea. The central part of it for Yang Mian seems to be the ubiquity of the images being selected. He chooses among the most universally known examples of Chinese landscape painting, from Fan Kuan to Zhu Da. It’s simple really, but no one else has ever done it. It is all just an extrapolation of what we register in the image, translated into pure color data. The statement is very direct and he’s just borrowing what’s already there. But he’s pushing it to a new extreme & the process, once again, is amazing. It’s incredible. The pieces are huge.

“Given that vision supposedly makes use of half the brain’s resources, it is no wonder that visual images exert a large impact on our thought processes. A single visual image can embody and express a great deal of information, and to analyze that information and its reliability can take more effort than the viewer is willing to expend. But if we are basing our knowledge of art history, or history, or current events on images, it is essential that we probe beyond an easy surface understanding. And only if we take the time to probe beyond the pretty surfaces of Yang Mian’s paintings do we finally arrive at this hard nugget of truth.”

-From Yang Mian’s catalog Essay, “Yang Mian Exposes an Essential Truth for Our Era” by Britta Erickson